Review | "Tramps!": A Documentary

Disruptive Embodiments: Queer Identity and the Aesthetics of Marginality

It is an admittedly arbitrary and perhaps revisionist exercise in imaginary history, yet one still possible to be pursued in good faith: attempting to trace a largely improvised, and hitherto unexamined, delineation of hidden relationships that, perhaps serendipitously, forge a common aesthetic path between seemingly incongruous eras, social milieus and cultural datasets.

In the spirit of this genealogical fantasy about intergenerational urgency, whose aim is an alternative interpretation of bequeathed legacy and improvised tradition, I will examine the idea of “glorious catastrophe” as a defining concept that resonated through quite a few 20th-century youth cults.

The “glorious catastrophe” concept denotes a conscious, persevering celebration of the marginal for what it is, without aspiring to accommodation, recognition or acceptance by the status quo, institutions and systemic acclaim.

The phrase per se was coined and best articulated in the writings of the seminal film-maker and artist Jack Smith (American, 1932-1989), a giant of 20th-century art, whose experimental multimedia work defined a specific, orgiastic, rebellious iteration of what he considered “baroque art”.

Smith's chaotic and prolific output, encompassing idiosyncratic exercises in photography, film, performance, theatre, activism and writing, was a constantly evolving ontology of supra-aesthetic delirium, a mesmerizing agglomeration of approximate encrustations, expressing more of a weltanschauung than following any definitive style, aspiring to cultivate an atmosphere instead of establishing any regime.

Incorporated into Smith's visual language, whose integrity is as strict as its refusal to compromise is absolute, one finds influences coming from many directions of invented rather than inherited history: scraps of seemingly random elements, like the artificial hyperbole of Hollywood glamour and the grittier enunciations of drag queen extravaganzas, mingle with a raucous crowd of misfits, gate crashers, and sideshow personas in a bacchanal of nonsensical narratives, implied deviance and obvious excess.

Their common denominator is a mythological essence that requires a suspension of disbelief to be appreciated beyond the realm of logic, sense, rationality and conformism.

For example, ornately bejewelled and extravagantly costumed characters are indiscriminately borrowed from antique burlesques, introducing the genius of vulgarity, but also from the loftier visions of grand opera, as if ennobled high culture refugees are seeking solace in the tawdry stages of travelling troupes and side-show attractions.

They indiscriminately rub shoulders with their poor relatives, like Arlecchini, Colombinas and Pulcinelli, kin of a similarly carnivalesque persuasion which has been recruited from the Commedia dell'arte, their recognizable, picturesque oddity invited by Smith, in his disciplinary role as a practising “baroque artist” who works with (imaginary yet alluring) “superstars”.

While populating his tableaux with disruptive embodiments of queer transgression and theatrical make-believe, Smith, the enforcer of a new, non-conforming “norm” displays the same ubothered nonchalance that “normal” directors might exhibit when casting for background extras, predictably filling out the margins of their non-baroque, realistic everyday scene with non-descript characters. And it is always a scene.

In Smith’s orgiastic vision, deterritorialized manifestations of theatrical provenance outline a semaphore for temporarily embarrassed representatives of stage nobility, impoverished aristocrats whose decadent apparitions are in turn themselves accosted by even more eccentric characters like erotic dancers, bearded women, dancing freaks, sensual mermaids, mystical fortune tellers and other exotic attractions, a whole lot of affected simulations becoming an unruly crowd that counter-intuitively coalesces into a surprisingly meaningful association of gender divergent, radically alienated and self-exiled Others

Uniting these exaggerated shadows of the recognisable for representing the alien is the idea of an identity that has repeatedly, and thus consciously, failed to accommodate any approach for integration into the real or even feign to approximate the realist – in crucial defiance, these physical embodiments of self-actualization, are fuelled by the vision of a sui generis conviction about otherworldly strangeness personified as an almost holy path towards sublime transcendence.

This highly introverted practice of existential assertion, whose core tenet is the indivisibility of the self, is simultaneously, visibly, audibly, actually persevering to claim public space and demand attention with a tenacity disarmingly performed as an ever-augmented spectacle of hyper-differentiated and maximally considered appearance, an instantly recognizable bird of an individualist paradise, uniquely unpaired, a queer being by any other name, residing permanently on the periphery of social complicity, where the outlaw meets desire, not with regret or in defeat, but triumphantly so.

The mid-1960s apex of Smith's career coincided with Susan Sontag's famous “Notes on ‘Camp’”, where the seminal concept of “failed seriousness” was introduced, a theatrical invention about ambitious aesthetic intentions gone wayward, exaggerations useful for histrionics and dramatizations which signified a vernacular perversion of the language of elitism, accidental democratization and involuntary desecration of whatever currently remains of unattainable glamour, intellectual status, and creative prestige that might still be afforded to the so-called serious dramatic arts.

A clearly Romantic principle of forlorn mysticism and existential ennui is thus extricated from overwhelmingly decadent exaggerations. This is especially evident in symbolic assemblages that unify stylized representations of the relationship between the human (i.e., the artificial or what can be represented) and the natural. These assemblages unveil for the audience a captivating glimpse of the melancholic sublime.

This sublime potentiality is viewed from the top of ruins, commemorating former civilizations and summoning ancient lore in the middle of a desolate landscape that signifies the adventurous contemporary. The sum of this highly charged mise en scène radiates with the effulgent turmoil of existential wanderlust, becoming a pictorialist surface that gleams attractively while obscuring vast, unconquered, and fascinating interiorities.

From this heroic yet reflective Romantic ideal—a blend of Northern introversion and metaphysical fatalism, stage-designed to invoke a lament for the classical, and unavoidably the baroque—one is called to imagine a sustainable credo for an army of the gloriously defeated: how else are we to explain the miracle by appointment witnessed in the multiple manifestations of fervent devotees that form a parade of the exceptional across the ages, demonstrating a common adherence to aberrant phenomenology?

The history of queer cultural production is linked to various underground art scenes, which provided refuge and inspiration for marginalized voices.

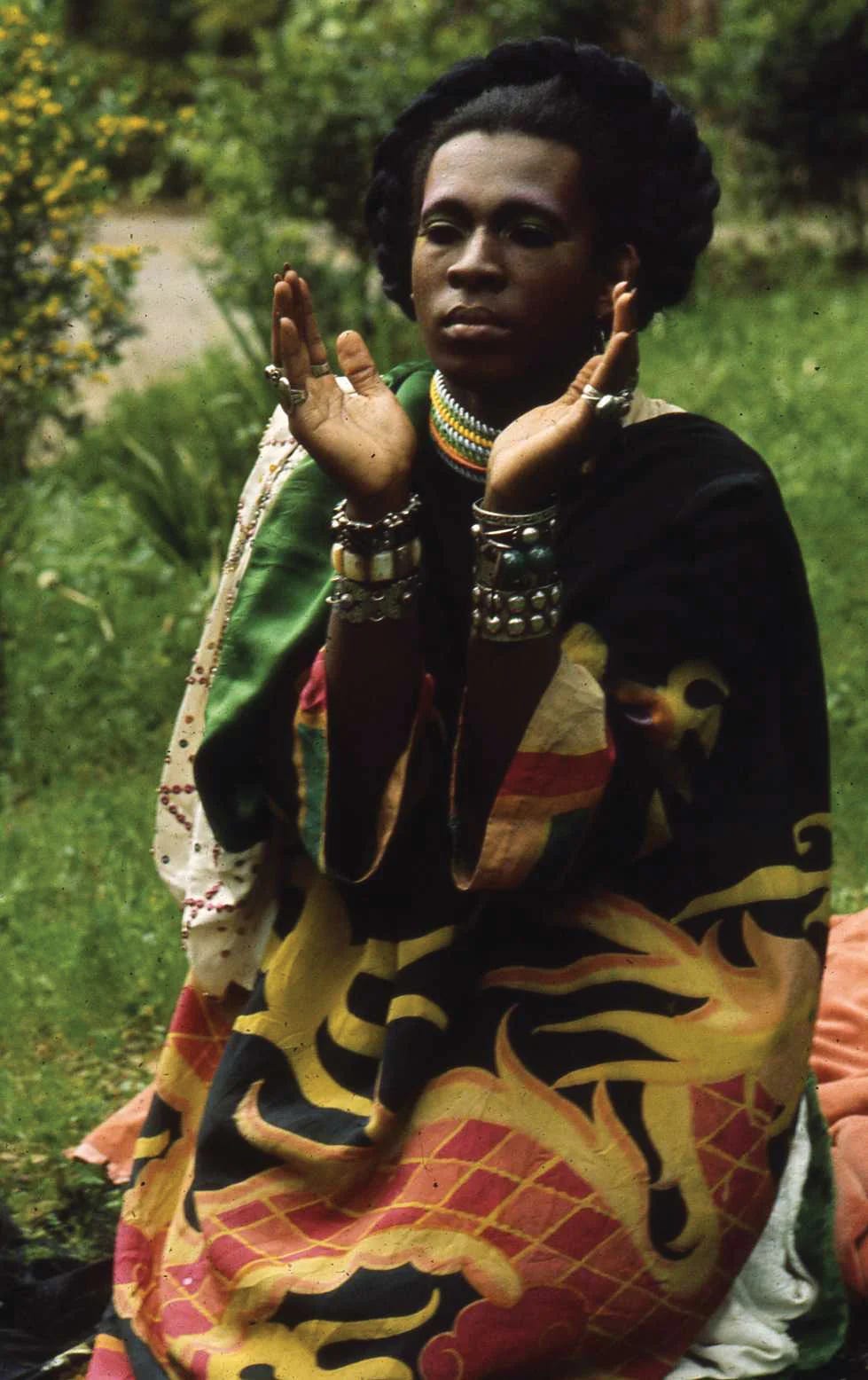

Figures like Jack Smith, with his experimental films and performances, and his muse/lover Mario Montez (see above), an icon of underground queer culture, exemplify this spirit.

These artists operate in liminal spaces, creating work that defies easy categorization and often incorporates elements of "camp" while addressing deeper political and philosophical implications.

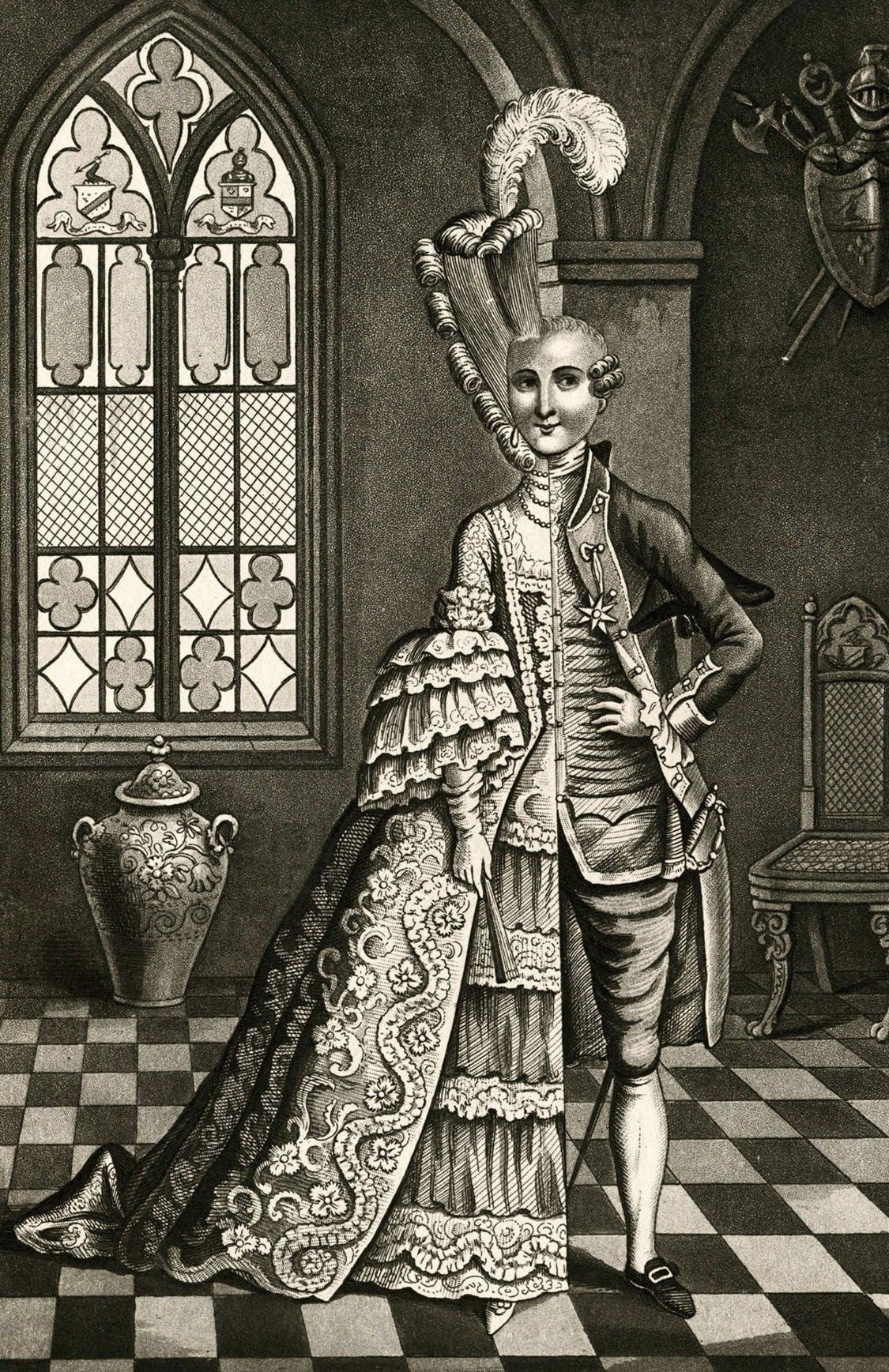

Larger-than-life-figures of embodied queerness, glorious catastrophe and failed seriousness, like the Chevalier d'Éon, Henry Cyril Paget, Cecil Beaton's Bright Young Things, The Cockettes and the “New Romantic” Blitz Kids, including the Taboo/Leigh Bowery aftermath, to name just a few examples of communal socio-aesthetic transgression amongst many others, are far from quaint theatrical devices or carnivalesque entertainment, forming a lineage of aesthetic rebellion in Western cultural history dating back to at least the 18th century and most certainly to the dawn of time.

From the Bright Young Things' decadent parties to the New Romantics' synthetic rococo futurism and the Cockettes’ non-stop exotic drag cabaret, from individual figures, like d'Éon's fluid gender presentation, Paget's theatrical excesses and others such as the unforgettable Marchesa Luisa Casati, a true Belle Époque queen of glorious catastrophe, or even today’s artist Daniel Lismore, each iteration reimagined identity and social belonging, embodying the elusive spirit of living as a work of art, the arc of their devastating manifestations bridging fin de siècle decadence and early 21st-century avant-garde socio-sartorial sculpture.

.

This spirit, fuelled by ambition, made possible by dedication, felt as a calling or even practised as an avocation, is usually intertwined with youthful nightlife, queer aesthetics and social subversion, always challenging normative boundaries through fashion, style, and artistic expression. An ever-progressing zeitgeist pageant, rather than expressing social dissent or engaging in dialectics, embodies the isolationist goal of self-imposed exile. It is a stance and worldview that follows a unique path (Sonderweg) by embracing its fatal flaws as superpowers.

This lineage of aesthetic rebellion represents a continuous thread of challenging social norms and exploring fluid identities through style and self-presentation.

.

Extravagant appearances, provocative visibility, and refusal to conform to any conditioned gaze: these characteristics impede integration with societal norms and challenge survival protocols, such as “passing”, the societal process of blending in often pursued by queer people via their performative compliance to conventional priorities in the name of survival.

Yet, somehow, these exaggerated behaviours and aesthetic statements become tactics of existential affirmation and actualization exactly because they are synonymous with the forbidden, the outcast, and the pathologized. By creating exclusivity out of exclusion, socio-aesthetic outlaws reclaim ostracism as self-imposed, using their strangeness as a visual and social warning sign that ultimately demarcates a safety zone from which normality, conformity, and even common sense are, in turn, themselves, excluded and repelled.

A good argument proposed about one seminal iteration of glorious catastrophe in popular conscience, pop culture and the public eye is the documentary “Tramps!” (UK 2022, directed by Kevin Hegge), a fascinating and in-depth film about the late '70s and early '80s micro-scene synonymous with a weekly party at a niche nightclub that spawned a visual and musical culture that ultimately still defines a surprising amount of contemporary creativity.

The story, familiar to friends of after-hour lore, begins in the twilight of the 1970s, as the embers of punk smouldered in London's underground, where a new flame ignited—one that would illuminate the city's nightlife with a dazzling if ephemeral, brilliance.

This was the birth of the New Romantics, a movement evocatively captured in all its contradictory glory by Kevin Hegge in his brilliant documentary "Tramps!", a film that serves as both a celebration and an elegy, charting the meteoric rise and tragic denouement of a subculture that redefined the boundaries of art, fashion, and identity in Thatcherite Britain.

At the heart of the New Romantic movement were the Blitz Kids, self-assigned architects of invented glamour, named after the infamous Covent Garden club that served as their nocturnal playground.

Steve Strange, the visionary party monster, public face, flamboyant doorman, fashion icon and de facto curator behind the Blitz Club, emerges as a central figure in this peculiar narrative. With his door policy as ruthless as it was arbitrary—famously turning away even Mick Jagger—Strange curated a space where creativity and outrageousness were the only currencies that mattered

Rusty Egan, Strange's partner in crime and the club's resident DJ provided the sonic backdrop to this socio-visual feast. His eclectic sets, blending everything from Kraftwerk to Bowie, became the heartbeat of a scene that pulsed with electric potential. Together, Strange and Egan didn't just run a club; they orchestrated a movement.

The Blitz club, a nondescript wine bar transformed into a Tuesday night haven for the aesthetically adventurous, sexually dissident and otherwise exceptional suddenly became the crucible in which this new movement was forged. An environment was cultivated, a community where the expression of self through fashion became an art form. The club's ethos, embodied in Strange's selective door policy, emphasized the importance of gatekeeping a safe space for individual creativity and sartorial risk-taking.

Within the Blitz's WW2-themed interiors, a most exceptional cast of characters assembled that would go on to shape the cultural landscape of the 1980s and beyond. Boy George, then known simply as George O'Dowd, manned the cloakroom, his acerbic wit already honed to a razor's edge. Spandau Ballet, under the management of the astute Steve Dagger, found their first audience here, their music becoming the soundtrack to the scene. Fashion students like Stephen Jones, Stephen Linnard, Kim Bowen and Michele Clapton experimented with looks that would eventually grace international runways, until today and presumably in the future.

Melissa Kaplan, a regular at the Blitz and later an influential stylist, epitomized this approach. Her combinations of vintage finds and DIY creations resulted in looks that were both meticulously constructed and delightfully haphazard. Kaplan's influence extended beyond the club, as she went on to style music videos and fashion editorials that brought the New Romantic aesthetic to a wider audience.

The New Romantic movement's impact extended far beyond fashion. Musically, it heralded the rise of synth-pop and the new wave, with bands like Visage, Ultravox, Culture Club and Sigue Sigue Sputnik, bringing the sound of the Blitz to the charts. The movement's visual aesthetic, characterized by dramatic makeup and gender-bending fashion, found its way into music videos and magazine spreads, influencing popular culture on a global scale.

However, the Blitz Kids' cultural significance lies not just in their artistic output, but in their embodiment of a "glorious catastrophe." This concept, rooted in the idea of embracing failure as a creative force, is key to understanding the movement's lasting impact. The New Romantics' willingness to push boundaries, to risk ridicule in pursuit of beauty and self-expression, created a space for experimentation and identity exploration that amounted to revolutionary risk-taking.

The queer semantics of the New Romantic movement are particularly noteworthy. In an era still marked by significant homophobia and rigid gender norms, the Blitz Kids created a temporary autonomous zone where non-normative identities could be celebrated and explored. The movement's embrace of androgyny and camp aesthetics challenged societal expectations and paved the way for greater acceptance of LGBTQ+ identities in mainstream culture.

Legendary figures like Leigh Bowery, who, a few years later, would become a shamanic figure at the equally influential Taboo club, took the New Romantic aesthetic to its logical extreme. Directly inspired by the Blitz Kids in so far as Bowery himself immigrated from Australia to London with the explicit goal of becoming a member of this specific tribe, which he admired in magazines like The Face and i-D, his transformative approach to fashion as a strictly personal medium of performance art pushed the boundaries of self-expression even further, influencing a new generation of artists and designers.

.

The legacy of the Blitz Kids and the New Romantic movement continues to resonate in contemporary culture. Their influence can be seen in the work of designers like the late Alexander McQueen and Gareth Pugh (to name but two of many), in the gender-fluid aesthetics of innumerable modern pop stars, not least Chappell Roan and Harry Styles, not to mention the ongoing dialogue about identity and self-expression in fashion and beyond.

Moreover, the movement's relationship with consumerism was complex. While the DIY ethos of many Blitz Kids challenged capitalist norms, the scene's focus on fashion and image also fed into the burgeoning youth market of the 1980s. This tension between subversion and co-optation is a recurring theme in subcultures, and the New Romantics were no exception.

In conclusion, the Blitz Kids and the New Romantic movement represent a pivotal moment in British cultural history. Their embrace of fashion as a form of radical self-invention, their challenging of gender norms, and their fusion of music, art, and style created a cultural legacy that continues to influence and inspire. By embodying and exemplifying the concepts of "glorious catastrophe" and "failed seriousness," they carved out a space for experimentation and identity exploration that was truly revolutionary. As we continue to grapple with questions of identity, self-expression, and the role of fashion in society, the lessons of the New Romantics remain as relevant as ever.

The New Romantic aesthetic was a deliberate rejection of punk's nihilism, embracing instead a form of elaborate neo-dandyism and quasi-absurd identitarian mash-ups, assemblages that drew inspiration from a kaleidoscope of sources.

Historical references collided with futuristic visions, creating a look that was simultaneously retrospective and forward-looking. This sartorial time-travel manifested, for example, in the juxtaposition of Edwardian frock coats with make-up directly inspired by a '50s science fiction B-movie, or Victorian bustles paired with synthesizer-inspired accessories made out of discarded techno-scraps

The movement's fashion ethos can only be understood truly through the lens of "failed seriousness," a concept that illuminates the inherent contradictions of intentions and outcomes in their radical approach. The Blitz Kids took their appearance with utmost gravity, yet the resulting looks often teetered on the edge of irrationality. This tension between earnestness and high camp, ambition and outlandishness, created a unique aesthetic language that spoke to the complexities of identity and self-expression.

The creation of "Tramps!" itself mirrors the DIY ethos of the New Romantics, with director Kevin Hegge piecing together a narrative that challenges conventional wisdom about the era. In an interview following the film's debut at BFI Flare, London LGBTQIA+ Film Festival, Hegge revealed the origins of the project and his motivations for exploring this oft-misunderstood cultural moment.

Hegge's journey into the world of the Blitz Kids began serendipitously, sparked by a chance encounter with filmmaker and DJ Jeffrey Hinton at a previous BFI Flare festival. This meeting opened doors to a network of artists and personalities who had been at the epicentre of the New Romantic scene. Hegge recalls his introduction to this world, stating that Hinton "took me to the East London club Vogue Fabrics. It was closed, but they opened for him. It was crazy." This anecdote perfectly encapsulates the enduring influence and mystique of the New Romantic figures, their ability to open closed doors persisting decades after their heyday.

The documentary's focus on lesser-known personalities and diverse artistic practices was a deliberate choice by Hegge. He explains, "I wanted to contradict things we are told about this era and go deeper into it, revealing links we don't often see. There's a lot of Boy George and Spandau Ballet out there. I don't think that's a very accurate depiction of the art-makers of that time."

This approach aligns with a redefinition of the New Romantics as part of a broader tradition of artistic eccentricity, looking beyond the movement's most famous faces to uncover a richer, more nuanced narrative, identifying a through line that connected the original Blitz Club scene which spawned the New Romantics movement as it was arbitrarily called in the popular press, and whose creative impetus resonated until the mid-to-late '80s, when formerly obscure figures like Leigh Bowery and newcomers like Trojan and Michael Clarke began to emanate from the same underground nightclub spaces, shifting the tenor of the scene from decorative and whimsical to a more aggressive, alienated and bizarre interpretation of decadent aestheticism.

Personalities like the legendary performance artist, musician and party host Leigh Bowery, along with his artist partner and companion Trojan, film-makers John Maybury and Baillie Walsh, choreographer Michael Clarke, chronicler Sue Tilley, artist (and Bowery widow) Nicola Bates and the entire scene orbiting the Taboo parties brought the entire cavalcade of aberrant stylizations to their monstrous conclusion.

This stridently uncompromising and disarmingly confrontational attitude was perhaps expressing a subconscious rage, its agitation and Dadaist acting out debatably influenced by the darkness descending on a generation faced with the devastation brought on by the AIDS epidemic.

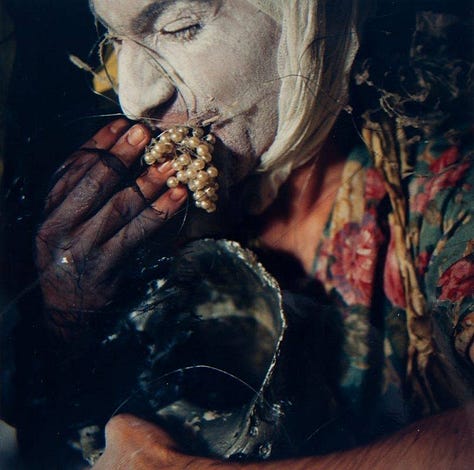

Of particular interest to Hegge is artist Trojan, whose disquieting “comedy” paintings feature prominently in the film, and whose early death at the age of 22 by a drug overdose turned his hysteric glamour into a persistent ghost haunting the queer imagination. This focus on someone usually (and unfairly) dismissed as Bowery’s sidekick (and tragic drug casualty) succinctly showcases the diversity of artistic expression within the scene and how closely this collective experience of a queer youth cult relates to abjection and tragedy.

In this spirit, Trojan, Leigh Bowery's equally outrageous flatmate and sometimes paramour, honed his craft of expressionism using the medium of personality. This process of becoming involved is a performative ritual in lore creation, involving and metabolizing undiagnosed mental illness, self-medication, self-harm and dangerously outré behaviour. Trojan’s everyday reality was an embodied and durational self-imposed experience designed for maximum impact, attention-seeking, and nihilist extroversion. This lifestyle-as-art often blurred the line between fashionable eccentricity, life-threatening pathology, and endurance art, if not freak-show grotesquerie. Trojan's extreme dedication to inimitable stunts exemplified his commitment to pushing the boundaries of self-invention-as-sacrificial-ritual.

"I wanted to take a fresh perspective and talk about the diversity of art practices happening at the time," Hegge notes regarding his concentration on lesser-known artists and minor figures, a choice that helps to paint a more complete picture of the creative ferment of the era, highlighting how material factors like free education and available central squats fostered a wide range of artistic endeavours.

If the New Romantic movement burned bright, the generation of queer creatives it represented was extinguished with equal ferocity. The advent of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s devastated the scene, claiming the lives of many of its most vibrant figures. Filmmaker’s John Maybury's description of this period as a "typhoon of death" is chilling in its accuracy.

"Tramps!" does not shy away from this painful history. The documentary becomes a memorial of sorts, paying tribute to those lost to the epidemic. The tragedy is compounded by the realization that many of these artists were cut down just as they were beginning to gain recognition for their work.

The AIDS crisis not only robbed the movement of its key players but also cast a pall over the hedonistic spirit that had defined it. The carefree attitudes towards sex and drugs that had characterized the scene became untenable in the face of a deadly epidemic. The New Romantic aesthetic, with its celebration of the queer body and alternative sensuality, took on a newfound poignancy.

Yet, even in this darkest hour, the resilience of the community shone through. Many artists, including Leigh Bowery, created work that directly confronted the reality of AIDS, turning their pain and anger into powerful statements of resistance.

The documentary's poignant acknowledgement of those lost to the AIDS crisis was another intentional choice by Hegge. He explains, "I wanted to show how many people were contributing to the scene. Obviously, talking about AIDS, I wanted to bring the people back to it. The whole creative community was decimated." This memorialization serves not only as a tribute but also as a reminder of the broader societal context in which the New Romantics and the Taboo crowd operated, their creative exuberance existing alongside profound loss and paralysing grief.

Perhaps most significantly, "Tramps!" seeks to highlight the ongoing relevance and vitality of the New Romantic ethos. Hegge's decision to focus on figures like Jeffrey Hinton, and Princess Julia, who continue to be active in the contemporary art and club scenes, was driven by a desire to challenge ageist assumptions about creativity and style. "I wanted to show people that, as you get older, you don't need to become bland," Hegge asserts. This perspective reframes the New Romantic movement not as a fleeting moment of youthful excess, but as a lifelong commitment to creative self-expression and nonconformity, a proud fealty to an ethos of difference.

In crafting "Tramps!", Hegge has not only documented a pivotal moment in cultural history but has also created a work that resonates with contemporary discussions about identity, artistic freedom, and the power of subcultures to shape society. By delving deep into the complexities and contradictions of the New Romantic scene, the documentary invites viewers to reconsider their assumptions about this era and to recognize its enduring influence on contemporary culture.

In this spirit of legacy, “Tramps!” introduces us to a cast of characters whose influence far outstripped their fleeting fame. Scarlett Cannon has been rightly presented as a mythical figure since a teenager, gracing the cover of i-D magazine and manning the box office at her Cha Cha party, happening right after the Blitz closed in 1980 every Tuesday night in the PVT room above the Heaven nightclub. With her shock of red hair and avant-garde face designs, Cannon is known as an embodiment of the severely committed style ethos that underpinned the movement, all before she turned 20. Princess Julia, a DJ and style icon in her own right, serves as a living archive of the era, her memories as sharp as her eyeliner ever was

.

Perhaps most poignantly, we encounter the late jewellery designer and fashion guru Judy Blame, whose innovative use of found objects in his accessory designs perfectly encapsulated the movement's ability to transmute the detritus of a decaying city into objects of desire. "I just made it look fucking fabulous," Blame declares in the film, a statement that could serve as the New Romantics' manifesto.

Central to the New Romantic narrative is the Warren Street squat, a dilapidated Georgian terrace house in central London that became an incubator for the movement's most outrageous ideas. Here, in conditions that teetered between appallingly squalid and excruciatingly chic, a generation of artists, musicians, and fashion designers found the freedom to experiment, literally taking shelter in the ruins of a crumbling empire.

At the crucible of creativity that was the Warren Street squat, reality reared its ugly face in the infamous bathroom, with its sodden floors necessitating rubber boots, an image that becomes a potent symbol in Hegge's documentary. It represents both the material deprivation that fuelled the New Romantics' creativity and the movement's ability to find beauty in the most unlikely places. This juxtaposition of glamour and grime, of high art and low living, speaks to the inherent contradictions that made the New Romantic movement so compelling.

The Warren Street squat wasn't just a place to live; it was an ongoing performance, a living installation that challenged the very notion of what art could be.

The New Romantic movement, in its brief but incandescent existence, embodied what the avant-garde film-maker Jack Smith termed "the glorious catastrophe." by embracing failure as an opportunity and celebrating the beauty of imperfection, finding its perfect expression in the DIY aesthetics and anarchic performances of the Blitz Kids.

Take, for instance, the notorious "Alternative Miss World" pageants organized by jewellery designer, artist and party host Andrew Logan, who is interviewed in the documentary and talks about his surrealist beauty pageants as a contemporaneous phenomenon that slightly prefigured and then overlapped with the New Romantics/Blitz Kids, still going strong later with the Leigh Bowery/Taboo axis and even occasionally happening today.

These, now legendary events, which turned the traditional beauty contest on its head, revelled in joyous amateurism, militant aesthetic anarchy and deviant humour. Contestants would cobble together outrageous costumes from whatever materials they could haphazardly scavenge, creating improbable looks that were as likely to fall apart on stage as they were to dazzle the audience, perhaps considered even more successful in their decrepit state than their potential to conjure a convincing facsimile of improvised glamour. The possibility of disaster was not just accepted but embraced, becoming an integral part of the performance.

This embrace of potential failure aligns closely with Susan Sontag's notion of "failed seriousness." The New Romantics, with their over-the-top fashions and theatrical personas, were deadly serious about their art, which, paradoxically was an act as far-fetched from earnestness and sincerity as possible, running on the fuel of pretend, make-believe, self-invention and all sorts of artificial theatricality.

This contradiction between the intensity of dedication and disaffection with conformism always fed into an undercurrent of irony, a tacit acknowledgement of the absurdity of their enterprise, a centrifugal force boosted by the circuitous tension between aspirational seriousness and critical self-awareness, aiming for a unique aesthetic (and moral) philosophy, one that was simultaneously profound and playful, oblivious to consensual reality yet aware of its own frivolous fragility.

Consider the music videos of the era, many of which are featured in "Tramps!". Bands like Visage and Ultravox created visual spectacles that were ambitious in their scope yet often charmingly naive in their execution. The result was a kind of accidental surrealism, or a too-ambitious perversion of arte povera, precariously teetering on the edge of the ridiculous as it traverses a tightrope of ideas strung high above its station.

This gap between purpose and realization became a space for unexpected beauty, enunciating the vocabulary of a burgeoning idiom that increasingly broke barriers and mixed elements of high style (fashion photography, cinematic monochrome, designer outfits, sophisticated references) with the urgent economy of a youth culture defined by its limited access to big budget resources (the immediate situationism of punk DIY practice, the prevailing conditions of economic recession and social decay).

While "Tramps!" primarily focuses on the aesthetic innovations of the New Romantics, it would be a mistake to view the movement as apolitical. The very act of dressing up in such extravagant fashion was a visible form of existential resistance against the grey austerity of Thatcherite Britain and the widespread malaise of homophobic hate that was considered socially acceptable back then.

The documentary touches on the fact that many of the scene's key players were living on unemployment benefits, using their dole money to fund their artistic enthusiasms. This was not mere hedonism, but a conscious rejection of the prevailing work ethic. By transforming themselves into living works of art, the New Romantics were asserting the value of creativity over productivity, of self-expression over conformity.

Moreover, the movement's embrace of gender fluidity and sexual ambiguity was revolutionary in a deeply conservative era. Figures like Boy George and Marilyn challenged societal norms simply by existing in public spaces. Their flamboyant androgyny was not just a fashion statement, but a political act, carving out space for queer identities in the mainstream consciousness.

The New Romantics' relationship with commerce was similarly complex. While they craved fame, there was an ambivalence towards mainstream means of achieving financial success, often risking everything in the name of supra-aesthetic integrity. This stands in stark contrast to today's influencer culture, where visibility is inextricably linked to commercial endorsements. The Blitz Kids' desire for recognition was rooted in a belief in the transformative power of art, rather than a pursuit of wealth.

As "Tramps!" illustrates, the influence of the New Romantics far outlived the movement itself. The documentary traces the careers of several Blitz Kids who went on to become significant figures in their respective fields. John Maybury's transition from experimental filmmaker to director of mainstream features is an example that demonstrates the scene's long-term impact on British cinema, just like Judy Blame’s creations adopted by fashion corporations like Christian Dior is another case of the street directly informing haute couture salons.

In the world of fashion, the DIY ethic of the New Romantics found expression in the work of designers like John Galliano, Rei Kawakubo and Vivienne Westwood, while impresarios like Suzanne Bartsch or Malcolm McLaren brought elements of the subculture to the global stage. The movement's influence can be seen in everything from Alexander McQueen's theatrical runway shows to the gender-fluid designs of contemporary labels.

Musically, the New Romantic sound, with its synthesis of punk energy and electronic experimentation, laid the groundwork for much of the pop and alternative music of the 1980s and beyond. Bands that emerged from the scene, such as Culture Club, Depeche Mode, Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet, achieved international success, spreading their synthetic pop aesthetic globally.

Perhaps most significantly, the New Romantics' questioning of gender norms and celebration of individual expression paved the way for today's more fluid understanding of identity. The movement's legacy can be seen in contemporary queer and trans activism, which continues to challenge societal norms and expand the boundaries of self-expression.

In documenting the rise and fall of the New Romantics, "Tramps!" does more than simply chronicle a moment in cultural history. It captures a spirit of creative freedom and radical self-expression that continues to resonate in our current era of conformity and commercialization.

The documentary's focus on lesser-known figures in the scene serves to highlight the movement's democratic nature. It wasn't just about the stars who made it big, but about a community of artists who collectively reshaped the cultural landscape. In doing so, "Tramps!" itself becomes a kind of glorious catastrophe, an ambitious attempt to capture a moment that was, by its very nature, ephemeral and elusive.

What emerges is a portrait of a movement that embraced failure as a creative strategy, that found beauty in imperfection, and that dared to imagine alternative ways of being in a hostile world. In an age of carefully curated social media personas and algorithmically driven culture, the messy, contradictory, and defiantly human spirit of the New Romantics feels more vital than ever.

The ultimate legacy of the Blitz Kids, as presented in "Tramps!", is not just about the music, fashion, or art they created. It's about the possibilities they opened up, the boundaries they pushed, and the lives they transformed. In their glorious failure to conform, they succeeded in expanding our understanding of what culture could be. And in doing so, they left an indelible mark on the fabric of British society and beyond, a splash of colour on the grey canvas of late Capitalism that continues to inspire and provoke to this day.

While "Tramps!" offers a vivid portrayal of the New Romantics as a distinctly 1980s phenomenon, a deeper analysis of the movement reveals its place within a longer lineage of artistic eccentricity and queer expression in British culture.

Though not explicitly argued in the documentary, one can infer that the Blitz Kids, with their flamboyant aesthetics and nocturnal revelry, echo earlier generations of creative outsiders who used fashion and performance to challenge societal norms.

Viewing the New Romantics through this historical lens, one cannot help but draw parallels to the Bright Young Things of the 1920s

.

This earlier cadre of bohemian socialites and aristocratic youth, chronicled by Evelyn Waugh in "Vile Bodies," similarly shocked polite society with their extravagant parties and gender-bending antics. Like the Blitz Kids five decades later, the Bright Young Things emerged in the aftermath of a global crisis (World War I) and embraced hedonism as a response to societal trauma, dominating London's social scene in the 1920s, and epitomizing a paradoxical blend of hedonistic frivolity and artistic innovation.

At the epicentre of this glittering milieu stood legendary photographer and artist Cecil Beaton, whose lens both captured and helped construct the mythos of this ephemeral era. Beaton's photographs, infused with a potent mixture of glamour and artifice, serve as both historical document and aesthetic manifesto, a cultural legacy of effete semantics offering a window into a world teetering on the precipice between self-indulgence and self-invention, aesthetic decadence and social decay.

The Bright Young Things' social circle was notably rich in queer subtext and coding. Their elaborate costume parties and theatrical personas provided a sanctioned space for gender play and sexual ambiguity. This performative aspect of their culture allowed for the expression of non-normative identities within the constraints of upper-class British society.

Beaton's portraits of figures like writer and later famous recluse Stephen Tennant and artist Rex Whistler are particularly revealing in this context. These images, with their emphasis on androgyny and aesthetic refinement, challenge conventional notions of masculinity and sexuality. The "budgerigar portrait" of Steven Runciman, with its deliberate echoes of Italian religious iconography, exemplifies Beaton's ability to infuse seemingly frivolous imagery with deeper cultural resonances and queer aesthetics

The concept of "camp," which would later be theorized by Susan Sontag, finds early expression in the Bright Young Things' aesthetic sensibilities. Their embrace of exaggeration, artifice, and stylization in both their art and their lives embodies the essence of camp as indulgent pretence and vital delusion, creating a visual and performative language that speaks to queer sensibilities while maintaining a veneer of plausible deniability.

The Bright Young Things' fascination with costume and disguise takes on particular significance when viewed through a queer lens of fluid performativity and identity construction. Their elaborate themed parties, “...Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties…” according to observer and chronicler of the '20s society scene Evelyn Waugh, can be read as a premonition of what later was club culture, with drag performances attached. These events allowed participants to experiment with alternative identities and social roles, prefiguring later queer theoretical concepts of gender as performance.

Beaton's own gender-bending self-portrait, posing as writer Elinor Glyn, further underscores the fluid nature of identity within this milieu. By convincingly embodying a female persona, Beaton challenges essentialist notions of gender and highlights the performative aspects of social roles. This photograph serves as a visual manifesto for the Bright Young Things' rejection of rigid categorizations and embrace of multiplicity.

The performative nature of the Bright Young Things' identities extends beyond gender and sexuality to encompass class and social status. Beaton's own trajectory, from middle-class outsider to high society darling and royal confidant, exemplifies the group's collective performance of identity. His meticulous construction of self-image, evident in his early self-portraits and later in his carefully curated public persona, reflects a broader cultural shift towards the commodification of personality.

The Bright Young Things' influence extends far beyond their own era, prefiguring future youth subcultures that would emerge in the latter half of the 20th century. Their emphasis on spectacle, performativity, and the blurring of boundaries between art and life finds echoes in movements like the New Romantic Blitz Kids of the 1980s.

The Blitz Kids shared the Bright Young Things' penchant for elaborate costumes and gender-bending aesthetics. Figures like Boy George, Marilyn, and Steve Strange embodied a new wave of queer visibility, pushing the boundaries of gender expression in popular culture. Like their 1920s predecessors, the Blitz Kids used fashion and performance as a means of constructing alternative identities and challenging societal norms, bringing elements of queer culture into the mainstream.

The movement's emphasis on visual spectacle and persona creation can be seen as a direct descendant of the Bright Young Things' approach to self-presentation and their fascination with artifice and glamour as a means of transcending the mundane realities of everyday life. In the economically depressed Britain of the early 1980s, these subcultures offered an escape into a world of fantasy and self-invention, much as the Bright Young Things had done in the aftermath of World War I.

The legacy of the Bright Young Things, as refracted through Beaton's lens and amplified by subsequent youth cultures, continues to exert a powerful influence on contemporary queer aesthetics and identity politics. Their embrace of camp, performative identities, and the blurring of boundaries between art and life resonates with current preoccupations with online self-(re)presentation and social media personas.

In the age of Instagram and TikTok, the carefully curated self-images of the Bright Young Things find new expression in the digital realm. The tension between authenticity and artifice that characterized Beaton's portraits is mirrored in contemporary debates about filters, photo editing, and the construction of online identities.

Moreover, the Bright Young Things' exploration of gender fluidity and non-normative sexualities prefigures current discussions around sexual identity and gender expression. Their playful approach to the construction of the personal aligns with contemporary understandings of gender as a spectrum rather than a binary, and their use of costume and performance as a means of self-expression resonates with modern drag culture and gender-nonconforming aesthetics.

The "glorious catastrophe" of the Bright Young Things – their simultaneous embodiment of transgression and privilege, innovation and decadence – continues to fascinate and provoke. Their legacy serves as a reminder of the power of art and performance to challenge social norms and create spaces for alternative identities, even as it raises questions about the limitations and contradictions inherent in such cultural movements.

In examining the Bright Young Things through the lens of queer theory and subcultural studies, we gain new insights into the complex interplay between sexuality, gender, class, and artistic expression. Their influence on subsequent youth cultures and their ongoing relevance to contemporary discussions of identity and performance underscore the enduring significance of this brief but brilliant moment in cultural history.

By drawing these historical connections, we enrich our understanding of the New Romantics not just as a 1980s fashion movement, but as part of an ongoing dialogue between marginalized identities and mainstream society. While "Tramps!" focuses primarily on the immediate context and impact of the movement, a critical analysis of the documentary inspires us to consider the New Romantics within this broader historical framework.

This perspective suggests that in every era, some use style, performance, and sheer force of personality to carve out spaces for alternative ways of being. The New Romantics, as portrayed in "Tramps!", can be seen as carrying forward this tradition, even if the documentary itself does not explicitly make these historical connections.

In the end, what emerges from this analysis is a portrait of subcultural rebellion as a kind of cultural relay race, with each generation passing the baton of nonconformity to the next. In their glorious, glamorous catastrophe, the New Romantics ran their leg of this race with unparalleled flamboyance. While "Tramps!" captures the immediate impact of their run, it also invites us to consider the longer race of which they were a part, the past from which they paved a present leading to the future, leaving viewers to ponder the movement's place in the broader context of creative nonconformity throughout history.

A vibrant ecosystem of thriving queer expression is thus revealed through this punctually recurring anachronism of meticulously irrelevant aesthetic dissidents, youth subcultures and style cults whose deviant gestures are only observed in the interstices of normative culture, challenging boundaries of gender, sexuality, and the very fabric of artistic production and cultural meaning.

Unravelling this thread means exploring the complex intersections between queer identity and marginalized cultural production, focusing not only on fine art, performance, and underground aesthetics but also studying the multiplicities of self-expression in the service of simply being, just existing and constantly becoming.

In contemporary Western contexts, identities such as non-binary people, pregnant fathers, fem boys and transgender male gay porn stars further complicate traditional understandings of gender and sexuality, embodying fluidity, and evolving expressions of human experience. These identities create new possibilities for being and becoming that resist, if not upend entirely, the stifling confines of prefabricated and binary taxonomy.

Universally, at the heart of queer cultural production lies a spirit of subversion, resonating with cultural archetypes like the Fool of the Tarot, the Joker of playing cards, court Jesters and Clowns in entertainment. The trickster's palette seems to be a weapon in the armament of queer archetypes and the cultural insurrection these figures embody.

Actualizing a queer sensibility in their disruptive potential, challenging norms and upending expectations, these personages, are all standard characters of history and popular entertainment. “Monsters” are present almost everywhere: from circus attractions to children's parties, from adult card games to Hollywood cartoon villains and horror movie franchises, these ready-mads, are just pre-assembled tokens of the globally ubiquitous and ancient court jester archetype.

A sarcastic symbol of rebellious disorder, the jester, speaking truth to power but crucially not interested in gaining any for itself, is constantly evoked by performers from the most sedate female impersonators and mainstream rock stars to the most extremist avant-garde figureheads like Jack Smith and Leigh Bowery.

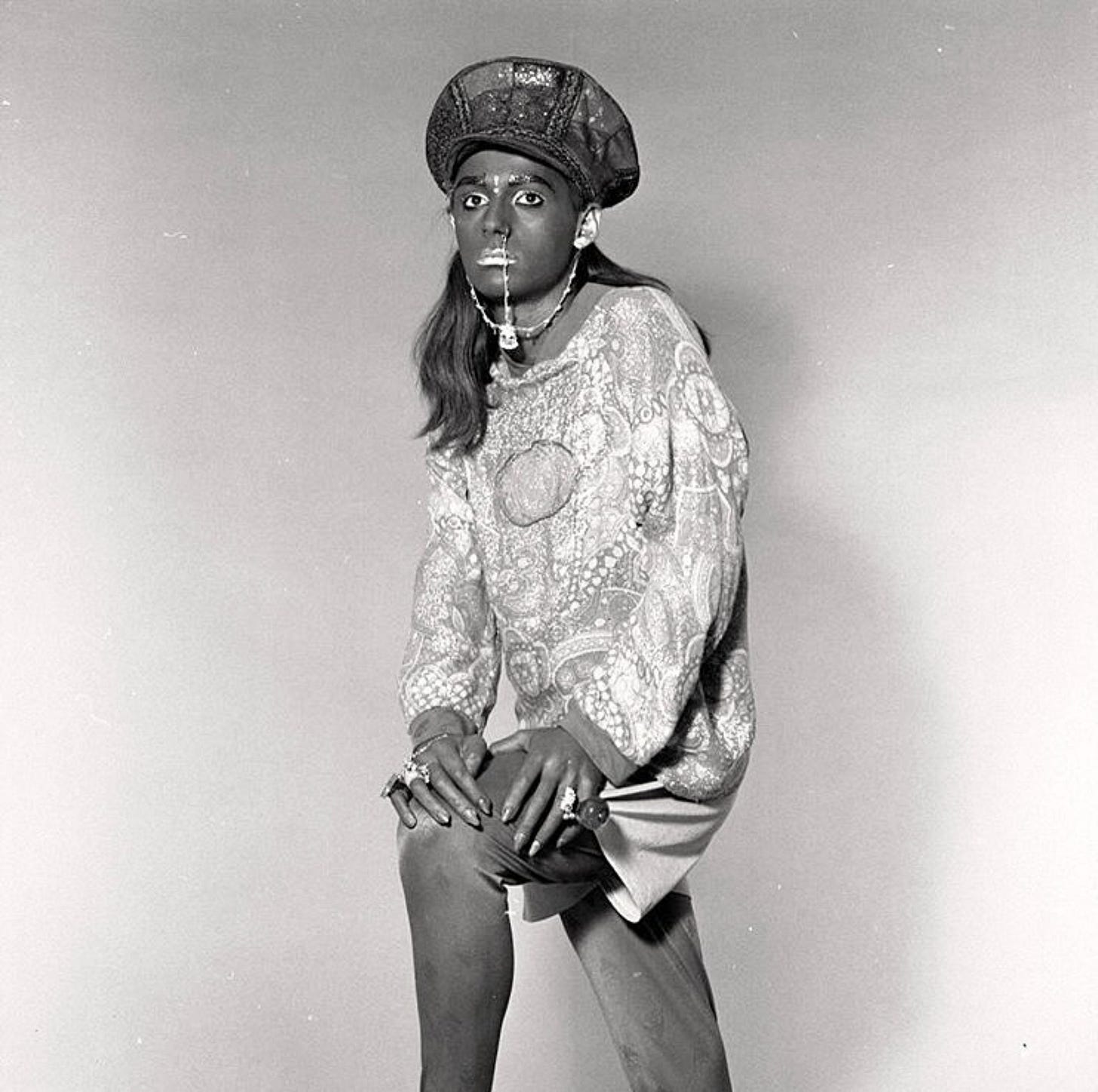

Bowery's work, involving extreme physical transformations and provocative performances, blurred the lines between art and life, by personifying a post-sexual totem free of any taboos, a shamanic being in the flesh, abdicating all responsibility to the performative nature of gender as a series of repeated acts creating the illusion of a stable identity.

Leigh Bowery, a phenomenon of corporeal transmutation and sartorial subversion, emerged from the conservative chrysalis of Sunshine, a Melbourne suburb, to metamorphose into London's most audacious performance artist. His journey from being the well-behaved progeny of Salvation Army administrators to becoming the embodiment of postmodern delirium was marked by an unrelenting pursuit of aesthetic radicalism.

In the crucible of 1980s London, Bowery's artistic genesis was catalysed by the Punk and New Wave ethos. He swiftly discarded the provincial vestiges of his antipodean origins, adopting an English accent and immersing himself in a milieu of conceptual art, gossip, and the transgressive allure of figures like Divine, David Bowie and other icons of queer iconography, some of them his nightlife comrades

.

Bowery's self-conscious shyness paradoxically fuelled his compulsion for spectacle, a dialectic masquerade of concealment and revelation that would define his oeuvre. His sartorial evolution traversed the terrain from romantic dandyism to a hyper-modern pastiche of excess. His "power suits" with ultra-padded shoulders and elongated pockets parodied the very notion of sartorial norms. As fashion trends oscillated, Bowery's aesthetic remained in perpetual flux, a rhizomatic exploration of glitter, Lycra, and sequins.

The nightclub Taboo became the proscenium for Bowery's weekly metamorphoses. His looks, ranging from the "Paki from Outer Space" fallen Hindu deities in glam-rock outfits, to the more abstract configurations involving light bulbs and theatrical putty, were not mere costumes but ontological propositions. Each ensemble was a deterritorialization of the body, a nomadic flight from fixed identity.

Bowery's artistic praxis extended beyond self-adornment to the reconfiguration of space. His council flat, with its "Star Trek" wallpaper and mirrored tiles, became a heterotopia of deviance, a site where normative spatial logics were upended. Even the doorbell, reprogrammed to emit sexual moans, subverted the mundane rituals of domestic life.

The physical discomfort intrinsic to Bowery's looks—the lacerating gaffer's tape, the infection-prone cheek piercings—spoke to a biopolitical resistance against the docile body. Pain became a vector of authenticity, a means of inscribing his artistic vision directly onto his flesh.

This corporeal dedication extended to his collaborators, or "slaves" as Bowery called his coterie of accomplices/friends, who were incorporated, sometimes literally, into his creations, like his wife Nicola who was herself worn as a human shield or ejected as a bloody newborn tumbling on stage from the ample folds of a voluminous skirt worn by Leigh.

Wearing a ratty grey wig and clashing yet dull attire, Bowery's daytime “every-man” persona was an uncanny and unsettling mix of abject ordinariness and indubitably his most subversive performance. Looking like a sex predator pretending to be a trustworthy adult or a mental patient who recently escaped from a high-security asylum, Bowery consciously evoked the spectre of a seriously disturbed individual attempting, in a most disquieting manner, to simulate normative appearances but most crucially, visibly failing in this pathetic effort at belonging.

The obvious evidence of such a catastrophe (social dysfunction, awkwardness, objectification of repulsion) - and the cost of failure (ostracized social status, uncomfortable interactions) as ultimate statements of glorious seriousness: in an almost scientific manner, Bowery proved that a personality like his could never belong in any normal setting even if he tried. Actually, the more casual his outfits were, the more unsettling he looked.

Through this “failed normal” persona, Bowery permanently destabilized the boundaries between deviance and normalcy. He forced a confrontation with societal anxieties and represented convincing versions of bogeyman authenticity.

His performances as a frontman of pop groups like the Quality Street Wrappers, Raw Sewage and Minty further blurred the distinctions between art and abjection. Notorious acts of defilement involving bodily fluids and self-exposure were not mere provocations but ontological experiments, challenging the very categories of subject and object.

Leigh Bowery's oeuvre epitomizes the concept of disruptive embodiments, serving as a paradigmatic example of how queer identity can be articulated through radical aesthetics of marginality. His corporeal transformations, which ranged from the grotesque to the sublime, challenged normative conceptions of beauty, gender, and selfhood. By adorning his body with outlandish costumes, prosthetics, and makeup, Bowery created a living canvas that defied categorization and destabilized the very notion of a fixed identity. His performances, whether in nightclubs or art galleries, functioned as embodied critiques of heteronormative society, forcing spectators to confront their own assumptions about the limits of human expression and desire vis-a-vis both the normal and the pathological.

Bowery not only asserted and questioned his own queer identity but also carved out a space for alternative modes of being, creating a visual language that spoke to the exceptional experience of being simultaneously the centre of attention and an outcast on the margins of society by choice.

The aesthetics of marginality in Bowery's work were not merely superficial but deeply intertwined with his lived experience as a queer artist navigating the complexities of the AIDS crisis and Thatcherite conservatism. His deliberate embracing of the abject—through performances involving both confrontational behaviours and extreme physical discomfort—can be read as a reclamation of the stigmatized queer body. By making a spectacle of the very elements that society deemed unclean or immoral, Bowery subverted the dominant discourse surrounding queer bodies and AIDS. His refusal to disclose his HIV status publicly, while simultaneously creating art that subverted the boundaries of physical integrity, speaks to the complex negotiations of visibility and privacy that many queer individuals face.

In this way, Bowery's work embodies a politics of resistance through aesthetics, using the marginalized body as a site of contestation and empowerment.

The queer heritage of Bowery's disruptive embodiments continues to resonate in contemporary discussions of othered identity and performance art. His work prefigured many of the concerns of queer theory, particularly in its deconstruction of gender norms and its emphasis on the performativity of identity. By constantly reinventing himself, Bowery demonstrated the fluidity and constructivism of identity categories, challenging essentialist notions of gender and sexuality.

Moreover, his ability to move between high art and subculture, exemplified by his collaborations with painter Lucian Freud and his performances in nightclubs, blurred the boundaries between different cultural spheres. This traversing of artistic and social hierarchies can be seen as a queer intervention in itself, disrupting not only bodily norms but also cultural categories. In this sense, Bowery's life and work serve as a powerful testament to the potential of queer aesthetics to challenge, transform, and reimagine the boundaries of art, identity, power and society.

Bowery's collaboration with Lucian Freud marked an incarnation of his body within the canon of high art. As a model, he maintained the same disciplined approach that characterized his own creations, viewing the process as an extension of his artistic practice. His presence in Freud's studio became a site of mutual influence, with Bowery subtly altering the paintings and importing the hierarchies of his private life into this new domain.

The legitimacy conferred by the Freud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art did not domesticate Bowery's radical aesthetics. His appearance at the opening, in a wide-skirted floral gown, with a matching ski-mask and Kaiser helmet, reasserted his commitment to self-invention in the face of institutional recognition.

Bowery's final performance, his secrecy about his impending death from AIDS-related illness, was shrouded in the same ambiguity and theatricality that characterized his life. His hospital-bound body, adorned with tubes and wires, became a final, inadvertent costume—one that his friends speculated he would have appropriated for a performance had it occurred to him.

In a final act of excess, Bowery's corporeal remains defied containment. The casket at his funeral proved to be too voluminous for its allocated space in the Australian soil, standing as a material metaphor for a life that consistently overflowed the boundaries of convention.

Leigh Bowery, in death as in life, remained an uncontainable force, too big to fit his own grave, becoming a perpetual challenge to the staid and confining geometries of a prefabricated existence.

Queer aesthetics, of course, have deep historical roots, and the way to interpret their echoes demands an ear attuned to the ever-changing vagaries of social context, anthropological environment, cultural idioms, evolving terminology, local dialect and historical circumstance. Sexual minorities and gender non-conforming people existed and triumphed against the adversities of marginalization, persecution and discrimination long before the term "Queer" was reclaimed in the late 1990s when it ceased to be a slur and became a universal passe-par-tout denominating and celebrating non-heterocentric gender identities and sexualities.

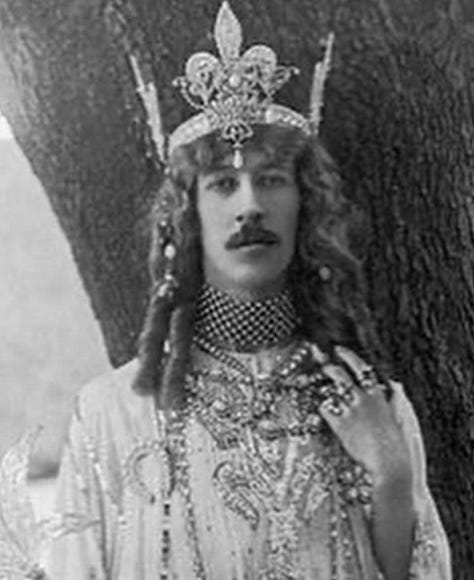

Figures like Henry Cyril Paget and the Chevalier d'Eon embodied queer sensibilities avant la lettre, challenging gender norms and societal hierarchies. These historical examples remind us that queer expression has always existed in a specifically performative and institutionally aberrant manner, illustrating a complex relationship between queer bodies with spectacle and power.

Such a spectacle of queer decadence is worth remembering, more so because it happened in the twilight of Victorian England, when the flamboyant figure of Henry Cyril Paget, 5th Marquess of Anglesey (1875-1905) emerged from the gloom of a precarious and stifling social climate still poisoned by the homophobic panic resulting from the tragic and very public Oscar Wilde trial and its aftermath.

Paget's trajectory from eccentric peer to bankrupt pariah serves as a compelling case study in the intersection of class, sexuality, and spectacle at the dawn of the 20th century. His penchant for extravagant costumes, jewellery, and theatrical productions transformed his ancestral seat, Plas Newydd, into a stage for his own baroque fantasies. The Marquess's conversion of the estate's chapel into the "Gaiety Theatre" stands as a metaphor for his subversion of tradition, replacing religious orthodoxy with the worship of artifice and self-expression.

The Marquess's performances, both on and off stage, can be read as a form of queer world-making. His gender-bending roles in pantomimes and adaptations of popular plays challenged the rigid binaries of Victorian society. By inhabiting traditionally female roles as a male performer, Paget destabilized not only gender norms but also class expectations, while simultaneously harkening back to theatrical traditions as old as Classical Greek theatre, Chinese opera and Shakespearean cross-sex casting.

The spectacle of an aristocrat cavorting on stage in "déclassé" roles served to both titillate and unsettle his audience, creating a space where transgression became entertainment.

Paget's sartorial choices further underscore his commitment to aesthetic extremism. His wardrobe, a riot of colour and texture, rejected the sombre masculinity expected of his station. The "morbidly fantastic" smoking suits, ermine lounge attire, and heliotrope silk dressing gowns speak to a refusal of normative taste. In adorning himself with a surfeit of jewels – both genuine and paste – Paget transformed his body into a glittering spectacle that defied easy categorization.

The Marquess's approach to sexuality and marriage was equally unconventional. His unconsummated union with his cousin-wife and subsequent separation hint at a queerness that extended beyond performative gestures and eccentric tics. In a society obsessed with lineage and succession, Paget's apparent disinterest in producing an heir represented a form of aberrant dereliction of duties that fuelled speculation about his sexual proclivities.

The inevitable financial collapse that followed Paget's extravagant lifestyle can be viewed as the culmination of a grand aesthetic project. His accumulation of debt – over £544,000 by 1904 – represents not merely fiscal irresponsibility but a commitment to deviating beyond the narrow path of bourgeois prudence. The subsequent auction of his possessions transformed private excess into a public spectacle, with "faithful (servant) Jerry" modelling the Marquess's garments for a jeering crowd.

This public humiliation, however, should not be seen as a simple morality tale of aristocratic decline. Instead, it represents the apotheosis of Paget's performative life. The auction itself became a theatrical event, with the Marquess's clothing serving as props in a drama of class resentment and fascination with decadence. The crowd's laughter at the sight of working-class Jerry in peacock blue silk pyjamas encapsulates the complex interplay of desire and derision that characterized the public response to Paget's excesses.

Again, the Marquess of Anglesey's life and downfall embody a form of queer resistance through spectacular failure. By pushing the boundaries of acceptable, even sensible, behaviour to their breaking point, Paget exposed the fragility of social norms and the seductive power of transgression. His refusal to conform to expectations of masculinity, fiscal responsibility, or patriarchal duty represents a form of radical negation that challenges the very foundations of Victorian society, if not the entirety of sensible, heterocentric morals.

Paget's brief, incandescent life would come to epitomize the paradoxes of fin de siècle decadence, transcending the boundaries of aristocratic propriety, gender norms, and fiscal prudence to become a living embodiment of aesthetic excess and queer performativity.

In the end, the Marquess of Anglesey's legacy lies not in any lasting artistic or cultural contributions, but in the very excessiveness of his lived experience. His life stands as a testament to the transformative potential of aesthetic extremism and the power of spectacle to disrupt social order. In his glorious catastrophe, we find a queer icon whose failure to be serious about the demands of his class and gender opened up new possibilities for imagining identity and desire in the modern world.

Stepping back a century or so, in the annals of 18th-century Europe, few figures embody the complexities of gender, power, and performance as profoundly as the Chevalier d'Eon. Born Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée d'Éon de Beaumont in 1728, this enigmatic personage traversed the boundaries of masculinity and femininity with a fluidity that continues to captivate and challenge contemporary discourse on queer identity

.

D'Eon's life unfolds as an assemblage of contradictions, a polyglottal narrative that resists simplification and demands nuanced interpretation. Initially serving as a diplomat and spy for Louis XV, d'Eon's early career was marked by conventionally masculine pursuits: fencing, military service, and clandestine operations. Yet, it was the latter half of their life, lived openly as a woman, that catapulted d'Eon into the realm of queer iconography.

The transition from male to female presentation was not merely a personal choice but a political act, one that interrogated the very foundations of gender in Enlightenment society. D'Eon's insistence on their female identity, despite having lived decades as a man, represents a prototype for the transgender narrative that predates modern conceptions of gender fluidity by centuries.

This deliberate destabilization of gender norms can be understood through the lens of glorious catastrophe—a concept that celebrates the fecund, and sometimes even beautiful, chaos of failed conformity. D'Eon's life was a perpetual performance, a grand spectacle that simultaneously adhered to and subverted societal expectations. Their adoption of feminine attire and mannerisms was not a retreat into convention but a radical act of self-creation.

The Chevalier's existence similarly embodies a particular brand of failed seriousness—a term that encapsulates the profound gravity with which d'Eon approached their gender presentation, coupled with the inherent absurdity of 18th-century gender roles and his own desecration of the norms.

Moreover, and particularly peculiar from a modern point of view which defines the codes of men's and women's appearance in a significantly more binary, opposed and mutually exclusive manner, d'Eon's performance of femininity was enacted in an era when wigs, make-up and elaborate sartorial ornamentation was a unisex standard. This multiplicity of nuances reveals an immanent tension within the potential performances of self that forced his contemporaries to confront their assumptions about the immutability of sex and gender.

D'Eon's life was a continuous negotiation between public persona and private reality. Their memoirs, rife with embellishments and self-mythologizing, blur the line between fact and fiction. This ambiguity serves not to diminish d'Eon's significance but to underscore the performative nature of all gender identities. In crafting a self-invented narrative that defied easy categorization, d'Eon became a living critique of the binary systems that sought to constrain them.

The Chevalier's legacy extends beyond their personal story, serving as a touchstone for discussions of gender nonconformity throughout history. D'Eon's refusal to be defined by the limited vocabulary of their time speaks to the enduring struggle of queer individuals to articulate identities that exist outside normative frameworks.

In examining d'Eon's life through a contemporary queer lens, we must resist the temptation to retrofit modern terminology onto historical figures. Instead, we can appreciate the Chevalier as a harbinger of queer possibility—a figure who, through their very existence, expanded the imaginative capacity of their era regarding gender expression.

The notion of glorious catastrophe finds its apotheosis in d'Eon's twilight years. Exiled in London, financially strained, yet unyielding in their commitment to their female identity, d'Eon's life became a testament to the power of personal truth over social convention. Their insistence on being buried in female attire, despite post-mortem revelations of their male physiology, stands as a final, defiant act of self-definition.

D'Eon's story intersects with broader currents of Enlightenment thought, challenging the period's emphasis on rationality and classification. Their fluid identity served as a living rebuke to the rigid categorizations that were beginning to dominate Western scientific and social discourse. In this way, the Chevalier becomes not just a queer icon but a philosophical provocateur, pushing against the boundaries of Enlightenment epistemology.

The concept of failed seriousness takes on new dimensions when applied to d'Eon's diplomatic career. Their effectiveness as a spy was arguably enhanced by their ability to move between genders, highlighting the performative nature of diplomacy itself. This blurring of lines between deception and authenticity raises profound questions about the nature of identity in both public and private spheres.

In conclusion, the Chevalier d'Eon stands as a figure of magnificent contradictions—a queer ancestor whose life defies easy categorization and continues to challenge our understanding of gender, performance, and identity. Their legacy is not one of resolution but of perpetual questioning, a reminder that the most profound truths often lie in the spaces between established categories, beyond the frontiers of closure.

D'Eon's life, viewed through the prism of modern queer theory and historical analysis, offers a compelling argument for the power of individual agency in the face of societal constraints and the enduring relevance of gender nonconformity in our ongoing discussions of identity and selfhood.

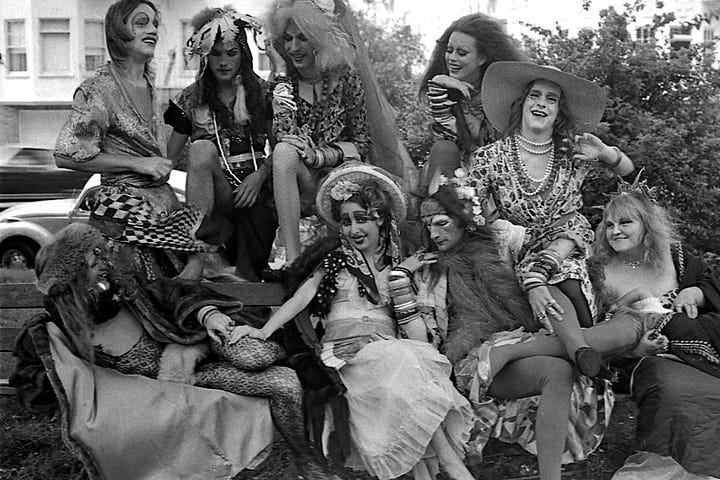

A few centuries later, on the Western USA seacoast, in the early 1970s, The Cockettes emerged as a vibrant link in this chain of aesthetic rebellion. This San Francisco-based drag troupe embraced a psychedelic, gender-fluid aesthetic that combined vintage clothing, glitter, and beards. Their flamboyant performances and DIY ethos challenged conventional notions of drag and theatrical presentation, influencing subsequent generations of performers and further blurring the boundaries of gender expression in popular culture

San Francisco, a city already renowned for its countercultural effervescence, was the appropriate environment for a drag troupe that would redefine the boundaries of performance art and gender expression. The Cockettes, the avant-garde collective founded by the enigmatic Hibiscus, were not merely performers but harbingers of a radical aesthetic and social revolution. Their performances, imbued with a psychedelic ethos and a subversive spirit, challenged the normative paradigms of theatre, gender, and sexuality.

The Cockettes were born out of the vibrant Haight-Ashbury scene, a crucible of hippie culture and radical experimentation. Founded in 1969 by Hibiscus, born George Edgerly Harris III, the troupe was a motley assemblage of gay men, women, and children who shared a penchant for outrageous costumes and a commitment to communal living. Hibiscus, a charismatic figure with a penchant for theatricality, envisioned the troupe as a living artwork, a continuous performance that blurred the lines between life and theatre.

Hibiscus's vision was deeply influenced by the countercultural movements of the 1960s, particularly the ethos of the Merry Pranksters and the radical theatre of The Living Theatre. The Cockettes' performances were a heady mix of drag, vaudeville, and psychedelic spectacle, characterized by their anarchic energy and DIY aesthetic. Their shows, often staged at the Palace Theater in North Beach, were legendary for their exuberance and unpredictability.

The Cockettes' performances were a riot of colour, glitter, and subversion. They parodied American musicals and Hollywood films, infusing them with a camp sensibility and a radical queer perspective. Shows like "Tinsel Tarts in a Hot Coma," "Pearls Over Shanghai," and "Journey to the Center of Uranus" were characterized by their elaborate costumes, surreal narratives, and a joyous disregard for conventional theatrical norms.

Their aesthetic was a bricolage of thrift-store glamour, vintage drag, and psychedelic excess. The performers, often adorned in glitter, feathers, and sequins, embodied a fluidity of gender and sexuality that was revolutionary for its time. The Cockettes' drag was not about illusion or passing but about celebrating the artifice and performativity of gender. This approach resonated with the burgeoning gay liberation movement, which sought to challenge and dismantle the rigid binaries of gender and sexuality.

Hibiscus, the spiritual and creative leader of the Cockettes, was a figure of almost mythic proportions. Born into a theatrical family, he was steeped in the world of performance from an early age. His early career in New York City, where he was involved in the Off-Off-Broadway scene, laid the groundwork for his later work with the Angels of Light troupe.

Hibiscus's approach to performance was deeply influenced by his experiences in the anti-war movement and the countercultural ethos of the 1960s. He famously appeared in the iconic "Flower Power" photograph, placing flowers in the barrels of soldiers' guns during a protest at the Pentagon. This act of peaceful defiance encapsulated his belief in the transformative power of art and performance.

With the Cockettes, Hibiscus sought to create a space where radical self-expression and communal living could flourish. His leadership was characterized by a commitment to artistic freedom and a rejection of commercialism. This often led to tensions within the troupe, particularly as they gained national attention and opportunities for mainstream success.

Among the many luminaries who passed through the ranks of the Cockettes, two figures stand out for their later contributions to popular culture: Sylvester and Divine.

Sylvester, who joined the Cockettes in the early 1970s, brought a unique blend of gospel-inflected vocals and androgynous glamour to the troupe. His performances were marked by their emotional intensity and vocal virtuosity, which often upstaged the more chaotic elements of the Cockettes' shows. Sylvester's time with the Cockettes was a formative period in his career, laying the groundwork for his later success as a disco superstar.

Divine, the larger-than-life drag persona created by Harris Glenn Milstead, also had a brief but memorable stint with the Cockettes. Known for his collaborations with filmmaker John Waters, Divine's performances with the Cockettes were characterized by their outrageousness and camp sensibility. In "Journey to the Center of Uranus," Divine famously performed the song "A Crab on Your Anus Means You're Loved" while dressed as a giant red lobster.

The Cockettes' influence on the world of drag and performance art is profound and enduring. Their radical approach to gender and performance prefigured many of the developments in queer theory and performance studies that would emerge in the following decades.

The brilliant 2002 documentary "The Cockettes," directed by David Weissman and Bill Weber, brought renewed attention to their work and cemented their place in the pantheon of countercultural icons.

Today, the Cockettes' influence can be seen in the work of contemporary artists and scholars who continue to explore the radical possibilities of gender and performance.

Ultimately, the story of queer aesthetics is one of resilience, creativity, and endless reinvention. It is a testament to the human capacity for self-expression and the power of art to challenge, inspire, and transform. As we continue to explore and celebrate these marginalized voices and visions, we participate in the ongoing queering of culture itself, creating spaces for new identities to emerge, new forms of expression to flourish, and new ways of understanding what it means to be human in all our glorious, foolish, and infinite diversity.

.

This journey through the landscapes of non-conforming and queer cultural production reveals not just a history of resistance and creativity, but a roadmap for future possibilities and a reminder that the most profound cultural innovations often emerge from the margins, from those who dare not only to imagine but to embody and implement different ways of being in the world.

It is through this lens that we can truly appreciate the radical potential of marginalized cultural production to reshape not just art, but the very fabric of society and new ways of understanding what it means to be human in all our glorious, foolish, and infinite diversity.

In embracing the expanded spectrum of being, we open ourselves to a world of existential possibilities, where the margins become centres of creativity, where the fool's step off the cliff becomes a dance of liberation, and where the disruptive power of non-conforming and queer aesthetics continues to reshape our understanding of art, identity, and human potential.

Text written by Panagiotis Chatzistefanou, exclusively for the Psychonaut Elite, Berlin, September 2024